DAY 4 – June 8, 2014 – “Dr. Suess’ Inspiration”

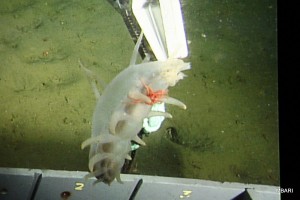

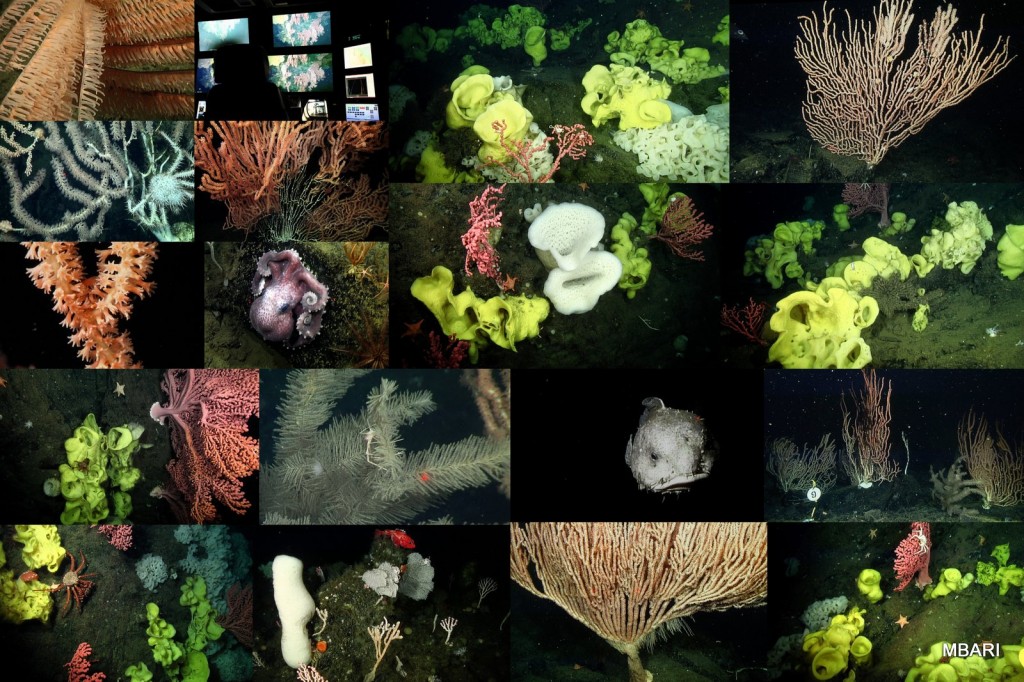

We didn’t think we could top yesterday, but we did. The diversity, the colors, the blob sculpins, oh my! It’s beginning to dawn on us that Sur Ridge is a very special place. Many of these corals can live hundreds of years if not even longer, and we’re starting the important process of documenting the presence of them not only for science, but also to tell their story and relay their images to the public to help foster that connection to their oceans; it’s not just a flat salty wet body of water with scary things underneath. It’s more incredible than even some of Dr. Suess’ books, as the following collage shows; and no, none of these pictures were photoshopped. Even long-tenured scientists, engineers and ROV pilots had to pick their jaws up off the floor when seeing these images live in the control room.

Tomorrow we wrap up this research cruise with a half-day of diving on the middle of Sur Ridge, an area we have yet to visit. I don’t care if it’s all mud, we’ve already hit paydirt.

Chad

><((((º>`·.¸¸.·´¯`·.¸.·´¯`·…¸><((((º>`·.¸¸.·´¯`·.¸.·´¯`·…¸><((((º>`·.¸¸.·´¯`·.¸.·´¯`·…><((((º>

DAY 3 – June 7, 2014 – “Goiter, Bamboo, Bubblegum and Picasso”

Today came with much anticipation, and it did not disappoint. Over two dives, we took different routes on the northeast portion of Sur Ridge. Each transect covered 300-400 meters in elevation over almost a kilometer in distance. At least eight different species of corals were seen today, probably more, actually. Bubblegum coral (Paragorgia sp) was the most abundant, with some individuals over two meters in width, perched along ridgelines to most efficiently capture food from the passing currents coming up the slope.

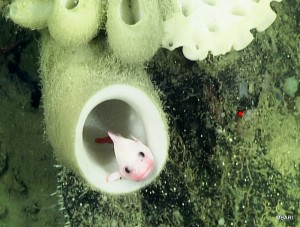

At least several species of bamboo corals were observed, and seemed to be more numerous than our dive near the same area last December. Long-lived black coral was also observed in several locations. Although their polyps were a bright golden, they get their name from the color of their skeletons. Some species of black coral can live thousands of years, but it’s undetermined how old the colonies seen today are. I must also note the large “goiter” and “Picasso” sponges, some of which spread over a meter in width and often housed various crabs and fish; it did look rather hospitable within.

We collected some bamboo coral with the ROV for a UC Santa Cruz biologist that is on board. Her lab plans on sectioning the base of the colonies to estimate ages of these colonies lay down rings much like trees do.

Tomorrow we will dive Sur Ridge again, perhaps the southern side. While there are not nearly the abundance and diversity of corals there (at least one dive has told us so), we expect a rich tapestry of geologic formations to keep us engaged. Please excuse the brevity of this post, but there’s a Giants game on in the galley….

Chad

><((((º>`·.¸¸.·´¯`·.¸.·´¯`·…¸><((((º>`·.¸¸.·´¯`·.¸.·´¯`·…¸><((((º>`·.¸¸.·´¯`·.¸.·´¯`·…><((((º>

DAY 2 – June 6, 2014 – “Finding a Needle in a Haystack (Make That a Cornstack 2 Miles Under the Ocean)”

Over five years ago, Dr. Jim Barry and MBARI placed a large bale of corn husks more than 10,000 feet deep outside of Monterey Bay. Sounds strange, right? However, this valuable stack of husks has been providing Dr. Barry valuable bits of information about carbon sequestration and ocean acidification. From corn husks, really? Let me attempt to explain. But wait, I almost forgot. We couldn’t FIND the corn bale for more than an hour. MBARI recently upgraded their ROV tracking software (remember, GPS doesn’t work underwater!), so the computer was giving us the wrong position for the ROV, making the apoint for the corn bale utterly useless. Talk about not being able to find your car in the parking lot! Alas, the incredible ROV pilots and MBARI engineers solved the problem and we established positional accuracy and found the corn bale!

Right, back to my explanation on why a corn bale was placed here…

As you may know, carbon dioxide, or CO2, is the main culprit of global warming, or climate change, whatever you want to call it. It’s responsible for the “greenhouse effect,” which traps infrared radiation within the Earth’s atmosphere. The more CO2 in the atmosphere, the more heat is trapped, and the higher global temperatures will rise. Dr. Barry had a novel idea: one way to sequester, or trap, a source of carbon dioxide might include sinking sources of cellulose that are normally burned on land, like this corn bale. Since many deep-sea organisms cannot digest cellulose, the carbon will not reach the ocean for many centuries, and Dr. Barry routinely comes here to measure oxygen levels within the bale as well as record observations on the general state of the bale’s integrity. So far it’s looking like it’s going to last for quite some time down there.

However, it appears that at least several species of galtheid crabs may be able to digest cellulose, and the corn bale was covered with hundreds of these crabs. This presented another golden opportunity for Dr. Barry to run a controlled experiment in the deep-sea. MBARI had a “benthic respiration system,” or BRS, custom built for this purpose. This car–sized contraption was placed very near the corn bale. Crabs from the corn bale were placed into respiration chambers by the ROV, which was not a trivial task. Every four hours over the next few months, oxygen levels will be dropped at incremental rates before being flushed with fresh seawater. These numerous intervals will give an average respiration rate for the crabs, which will serve as a baseline for the addition of seawater with higher levels of CO2, which is pumped from bags on the respirometer. This experiment will test the crabs’ tolerance of high CO2 levels, an extrapolation of what is currently happening to the world’s oceans. Each year about 1/4th of our CO2 emissions are absorbed through the sea surface. That extra CO2 reacts with ocean waters to make the oceans more acidic. Deep–sea animals cannot tolerate a rapid rise in pH, and they will be among the first to suffer dire consequences if humans don’t take steps to abate CO2 emissions over the next few decades.

Everyone on board is buzzing about tomorrow’s dive to Sur Ridge, as it will be purely exploratory in nature. No transects, no BRS, no cores. The control room is sure to be standing-room only. Just the anticipation of what we might find around each boulder, nook, hill and cranny. Last December, we discovered deep-sea corals at Sur Ridge, so the dive should offer colorful images of large assemblages of slow-growing corals and sponges, and who knows, maybe something more.

Chad

><((((º>`·.¸¸.·´¯`·.¸.·´¯`·…¸><((((º>`·.¸¸.·´¯`·.¸.·´¯`·…¸><((((º>`·.¸¸.·´¯`·.¸.·´¯`·…><((((º>

DAY 1 – June 5, 2014 – “Sea Pig Rodeo”

Writing a blog at 7 PM on the same day of a 5 AM boarding time does not bode well. Bear with me.

Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) invited Sanctuary scientists (two of us on board) along on this five-day research cruise to help out (although there won’t be near the volume of sediment samples to process…*grin*) as we have planned to re-visit two targets we hit last December: a sunken 40-foot shipping container that was lost and found in 2004, and Sur Ridge, a small 400 meter high “hill” about the size of Manhattan where we discovered rare deep-sea corals and even vesicomyid clams (they have a symbiotic relationship with methane-loving bacteria in their gut…which is what I need after that surf and turf dinner)

After pushing off, MBARI scientists recovered a sediment trap in Monterey Bay before moving on to a dive on the shipping container. Once the ROV “Doc Ricketts” arrived at 1,280 meters below the surface, we briefly surveyed the container itself (hasn’t changed much in 6 months) and proceeded to collect a species of sea cucumber (Scotoplanes) that is almost always found associated with a juvenile crab (species uncertain) taking a ride on its ventral side. We rarely have seen this crab (at least at this stage in life) alone out in the open, so the leading theory is that the sea cucumber (also affectionately known as a “sea pig”) provides protection from being eaten. Or, as Dr. Jim Barry postulates, maybe each of them just “needed a hug.”

Tomorrow MBARI will be conducting the deepest dive of the cruise. MBARI sank a large bale of corn husks 10,500 feet to the seafloor five years ago in order to evaluate its rate of decay and effects on seafloor animals. MBARI will also be installing a benthic respiration system to measure respiration rates of galetheid crabs common at abyssal depths. More about this experiment tomorrow.

An abbreviated MBARI cruise plan can be found here.

Don’t forget, you can receive more frequent updates if you follow us on Twitter @MBNMS!

Now that I’ve had two desserts tonight, it’s time to digest this sugary goodness with an early bedtime.

Chad King (@chadk21)