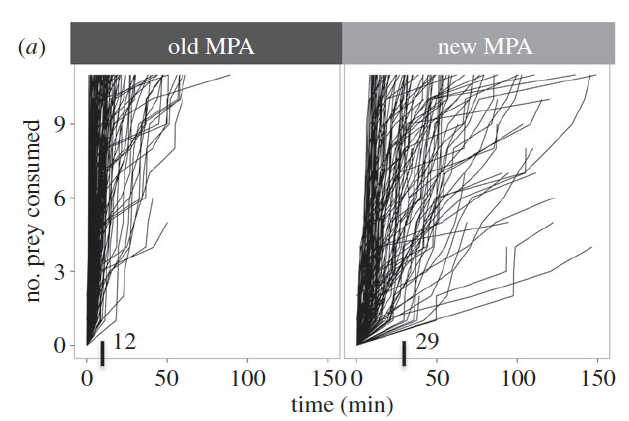

Humans have restructured food webs and ecosystems by depleting biomass, reducing size structure and altering traits of consumers. However, few studies have examined the ecological impacts of human-induced trait changes across large spatial and temporal scales and species assemblages. We compared behavioral traits and predation rates by predatory fishes on standard squid prey in protected areas of different protection levels and ages, and found that predation rates were 6.5 times greater at old, no-take (greater than 40 years) relative to new, predominantly partial-take areas (~8 years), even accounting for differences in predatory fish abundance, body size and composition across sites. Individual fishes in old protected areas consumed prey at nearly twice the rate of fishes of the same species and size at new protected areas. Predatory fish exhibited on average 50% longer flight initiation distance and lower willingness to forage at new protected areas, which partially explains lower foraging rates at new relative to old protected areas. Our experiments demonstrate that humans can effect changes in functionally important behavioral traits of predator guilds at large (30 km) spatial scales within managed areas, which require protection for multiple generations of predators to recover bold phenotypes and predation rates, even as abundance rebounds.

This paper appears in April 2019 issue of the Proceedings of the Royal Society B.