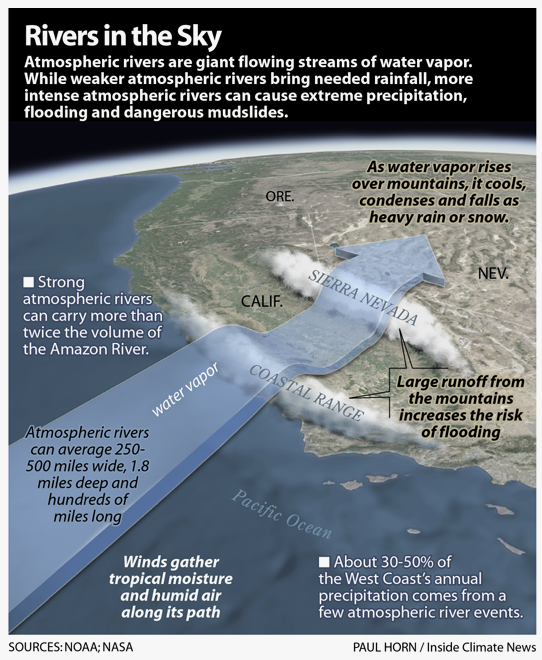

An increase in the frequency and severity of summer wild fires and winter storm events threatens endangered black abalone along the rocky intertidal of central California. There is an emerging combination that can lead to multiple, localized black abalone mass mortality events (MMEs). First, summer wildfires in California expose and alter soils in watersheds, leaving burn scars on the landscape vulnerable to mobilization during the following 1-2 years. Then add an atmospheric river event, which causes 92% of the west coast’s heaviest 3-day rain events and mobilizes sediment within burn scars. Intense downpours create powerful debris flows, which violently transport thousands of tons of rock, dirt, and tree trunks down the watershed and onto the intertidal. Thus wild fires + atmospheric rivers = debris flows, and this spells disaster for black abalone populations where debris flows meet the ocean.

Black abalone (Haliotis cracherodii) occurs along much of the rocky intertidal within Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Following the listing of white abalone in southern California, black abalone was the second marine invertebrate species listed as endangered. NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) issued a final rule to list black abalone as endangered under the ESA in February 2009, and critical black abalone habitat was designated in November 2011.

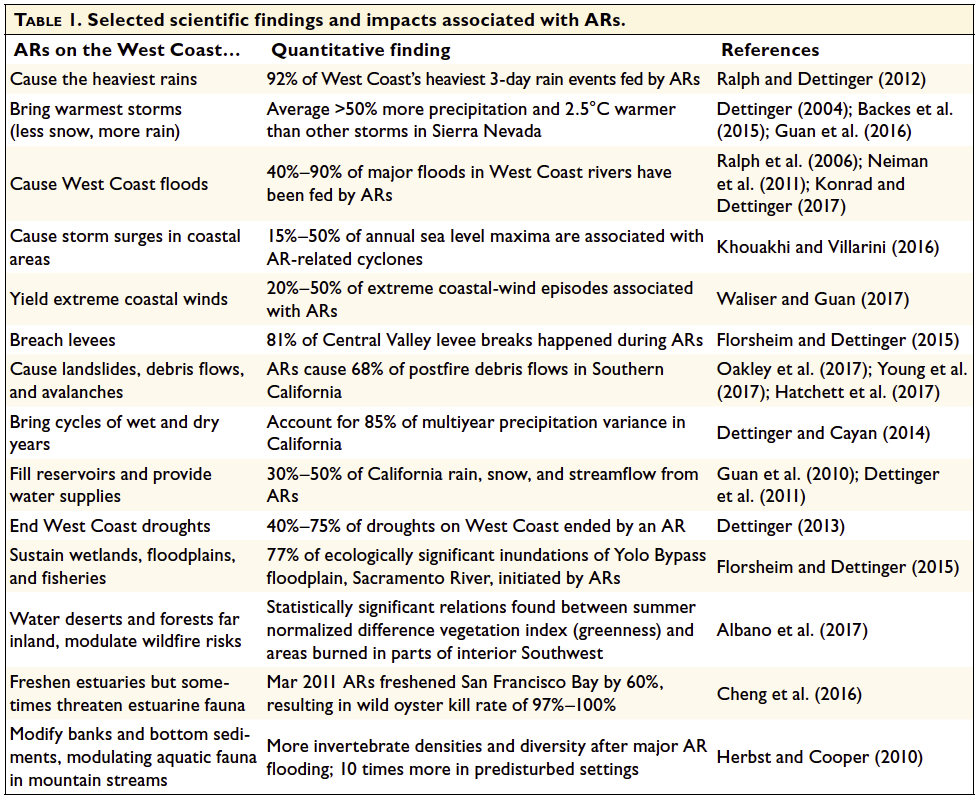

The term “atmospheric river” (AR) has only recently entered the public lexicon (Ralph et al. 2019), and the effects of ARs are receiving more attention (see Table 1). The most recent AR in central California began late January 26th and ended January 29, 2021. Reports indicated intense flooding, debris flows, and mudslides occurred throughout central and parts of southern California. Areas along the coastal mountains of Big Sur in central California received up to 15 inches of rain in three tumultuous days. Highway 1, the main route through scenic Big Sur, was particularly hard hit in areas where the Dolan Fire scarred the mountains and watersheds above the roadway. The Dolan Fire, which began August 18, 2020 and considered controlled on December 31, 2020, burned 125,000 acres and covered 20 miles of Highway 1 (from postmile marker 35.2 to 15.2). Part of the highway washed out at Rat Creek as the culvert was overwhelmed by debris, and will remain closed for several months to rebuild access across the new chasm.

Within the Dolan fire scar, several creeks and seasonal watersheds became violent debris flows, with boulders, rocks, tree trunks, and mud blasting downward to the ocean. This material generated debris fans where the outlets met the ocean, burying the intertidal under tons of earth and turning the ocean a dark brown color. Burned tree trunks litter the intertidal of Big Sur, as the ocean carries them both up and down the coast, battering into other intertidal areas and, in some cases, wedging into boulder fields or becoming temporarily stranded high up the shoreline.

At some intersections of creek and ocean, black abalone have been buried under tons of material carried down a watershed burned by 2020 wildfires. At the margins of the debris fan, black abalone were found partially or completely buried and struggling to survive. In extreme cases black abalone were found alive but stranded and motionless on top of the new sand, leaving them vulnerable to predators. Efforts are underway to rescue these burials. In this kind of an emergency situation, resources from multiple agencies were marshalled. This MARINe-based effort is supervised by Dr. Peter Raimondi and led in the field by doctoral student Wendy Bragg from UC Santa Cruz with cooperation from NMFS, CDFW, and the sanctuary. Due to the sensitive nature of this event, location information is not being shared with the public.

For more information about the involvement of sanctuary staff and this effort, feel free to contact Dr. Steve Lonhart at Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary (steve.lonhart at noaa.gov).

Related stories in the news: