Shark populations worldwide have experienced significant declines in recent decades. In order to shape management to best protect remaining shark populations, it is crucial that we increase our understanding of these apex predators through population assessment and monitoring. Globally, white sharks (Carcharodron carcharias) have three genetically distinct populations: one in the Northeast Pacific that includes West Coast Sanctuary waters, one in Australia/New Zealand, and one in South Africa.

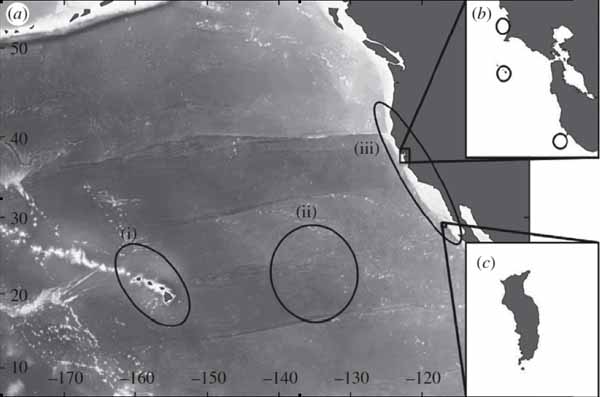

Historically, the difficulty of capturing white sharks and the very brief observation times available to researchers make it difficult to quantitatively study this species. Past studies using satellite tags to track white shark migrations provided a basic understanding of the Northeast Pacific population’s congregation areas and migration routes. We now know that “our” white sharks migrate annually from aggregation sites along the central California coast (Tomales Point, Farallon Islands, and Año Nuevo Island) and Guadalupe Island, Mexico across the Northeast Pacific to other focal use areas around the Hawaiian Islands and the “White Shark Café,” an area between Baja California and Hawaii (Figure 1). This migration usually occurs around the month of January. The white sharks spend about half the year in these areas before traveling back to the North American West Coast in August, generally returning to the same coastal areas each year. Thus, the sharks found in central California sanctuary waters from August to January remain separate from the group that inhabits the waters around Guadalupe Island during the same period.

A team of researchers led by Taylor Chapple (UC Davis) and Dr. Barbara Block (Stanford University) realized that since the sharks return to the same coastal regions year after year, it would be feasible to conduct a study estimating the size of the region’s white shark population. From September to January in 2006, 2007, and 2008, Chapple and Block’s team conducted research in the coastal waters off Tomales Point and the Farallon Islands. They used small boats to position themselves in areas where white sharks were congregating, and employed seal-shaped decoys on fishing line and small pieces of bait to attract sharks into photographic range (see attached video). Photographs of white shark dorsal fins were taken and used to identify individuals, since – like human fingerprints – the jagged edge of each individual’s dorsal fin is unique. Over the course of the three research seasons, the team collected 321 photographs of sufficient quality of white shark dorsal fins, and was able to identify 130 individuals by eye (including 69 males, 19 females, and 42 of unknown sex).

They then used a statistical model to extrapolate that there were a total of 219 adult and sub-adult white sharks in the central California region. Sub-adults are about 8-9 feet in length, with a diet that has shifted in focus from fish to marine mammals. Adults have reached sexual maturity, and are usually 13-15 feet in length. Prior to this effort, a census of white sharks had never before been conducted in this manner. The study, published recently in the journal Biology Letters, has resulted in the most rigorous scientific estimate of any white shark population in the world.

Mexico’s Guadalupe Island is believed to harbor an even smaller population of white sharks, so the total Northeast Pacific population is now thought to be approximately double the central California estimate of 219. Even if all age-classes were included in this estimate, it would still represent a much smaller number than the estimated populations of other large marine predators in the region (by comparison there are about 1145 orcas in the Northeast Pacific and about 1526 polar bears in the South Beaufort Sea). Given the larger range of white sharks and an absence of historic population reduction by humans, the very low white shark population estimate has been a particularly surprising result.

This small population size does seem to correlate with previous studies that have documented low genetic diversity in white sharks, as low genetic diversity is generally aligned with low population abundance. But the result leaves us with many unanswered questions. Do white sharks simply have a naturally low carrying capacity? Have anthropogenic pressures such as fishing mortality or prey reduction of pinnipeds adversely impacted white sharks and diminished their abundance? Chapple and Block’s groundbreaking census clearly defines the central California white shark population at one point in time, but it does not tell us how the current population compares to historic population sizes. Further research will be needed to indicate whether our white shark population is experiencing a trend of growth, decline, or stability.

The white shark census provides a critical element of any long-term monitoring effort: baseline data that will increase our understanding of natural population dynamics and anthropogenic impacts in the future. Additionally, the low estimate of white shark abundance should remind us of the critical need to protect and monitor this charismatic species that plays an important role in maintaining the health of marine systems.

Counting Sharks YouTube video (49 sec).

The video includes clips from the photo-census study and also from earlier studies that placed satellite-tracking tags on white sharks. Videography courtesy of Taylor Chapple.

Figure 1. (a) Known white shark focal use areas in the Northeast Pacific Ocean. (i) Slope and offshore waters around Hawaii, (ii) the White Shark ‘Cafe´’, and (iii) North American shelf waters, comprised of (b) aggregation sites off Central California (open circles from north to south: Tomales Point, Farallon Islands, Año Nuevo Island) and (c) Guadalupe Island, Mexico. (Figure from Chapple et al., 2011).

Chapple, T.K., Jorgensen, S.J., Anderson, S.D., Kanive, P.E., Klimley, P., Botsford, L.W. and B.A. Block. 2011. A first estimate of white shark, Carcharodon carcharias, abundance off Central California. Biology Letters, published online 9 March 2011 doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2011.0124