Sea urchins, and in particular purple urchins (Strongylocentrotus purpuratus), have been increasingly conspicuous members of Monterey Bay kelp forests since 2014. In some cases, these urchins are converting the kelp forest into a very different community, one dominated by urchins and turf algae.

Dr. Jim Watanabe, a local kelp forest expert, dove on 30 June 2017 with his students at a site between Hopkins Marine Station and Lovers Point and found the area had become completely deforested by sea urchin grazing. “There’s nothing but crustose corallines and patches of strawberry anemones left,” Dr. Watanabe noted.

As a lecturer at Stanford University’s Hopkins Marine Station, Dr. Watanabe teaches a summer course entitled the Ecology & Conservation Biology of Kelp Forests. He and his students dive sites in Monterey Bay every summer, and he has first-hand observations of the continued spread of deforestation from Point Pinos towards Hopkins.

“A few of the taller outcrops still have some sessile invertebrates left, but the extensive cover of compound tunicates, bryozoans, sponges, hydroids, and small red algae is gone. There are highly dense areas of purple urchins and larger red urchins too, although the reds are not as numerous as the purple urchins.”

During typical summers in Monterey Bay, when kelp forests grow rapidly due to plentiful sunlight and nutrient rich waters, the giant kelp Macrocystis pyrifera fringes the coastline from the Breakwater to Point Pinos. “If you examine the coastline of Pacific Grove and notice the kelp canopy is absent this summer, I suspect it is due to deforestation by sea urchins,” said Watanabe. Urchins consumed the kelp before it could grow to the surface.

But the large number of urchins has been around the last couple of years, so why the change this summer? Dr. Watanabe has an idea.

“I suspect that stretch between Hopkins and Lovers just lost too much of its kelp canopy over the winter, and the urchins began feeding on the remaining kelp after their localized supply of drift kelp disappeared.” Each winter most of the kelp is naturally removed by storms and high surge.

Like abalone, urchins are typically hidden in cracks and crevices of the rocky reef, avoiding predators while waiting for detached kelp to drift by. Urchins use hundreds of tiny tubefeet to both crawl on the reef and to grab kelp, which they then shred using five impressive knife-like teeth.

When drift kelp is scarce, urchins are forced to actively forage, emerging from the cracks and crevices to feed on attached algae. Often this results in urchins grazing on healthy kelp, and as new kelp initiate growth in the spring, urchins quickly graze them down, preventing any from reaching the surface to form the kelp canopy Monterey Bay residents are used to seeing each summer.

However, there are still some patches of healthy kelp forests, and Dr. Watanabe and his students have been diving in those areas too.

“All the sites that still have a surface canopy seem normal, although there are lots of urchins in those sites too – they are just not grazing actively on the kelp. The benthic red algae in those sites look very lush and healthy this year – dark red colors, lots of diversity – and lots of species that I have not seen much of since the warm water events of the past few years. So that’s good to see,” Dr. Watanabe said.

So what’s the deal with these urchins?

Sea urchins are a typical inhabitant of kelp forests in California. Successful reproduction and recruitment (i.e. when pelagic larvae settle onto a reef) is sporadic, leading to boom and bust years. Urchins live several years and are generally restricted to cracks and crevices.

Dr. Tom Ebert, Professor Emeritus at San Diego State University, is a world-renowned expert on sea urchin growth.

“Purple sea urchins get to be about 1.0-1.5 cm in their first year, more or less. If one starts at 1.5 cm (i.e. 1 yr old), the annual growth increment (change in diameter) would be about 1.2 cm, so a 2 yr old would be 2.7 cm in diameter,” Ebert said. Each year the increase declines, and this can vary regionally and by species.

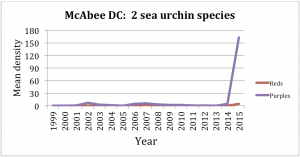

Urchin numbers skyrocketed in 2014. A kelp forest monitoring program managed by PISCO (Partnership for Interdisciplinary Studies of Coastal Oceans) at UC Santa Cruz has been counting sea urchins in central California since 1999. As can be seen in the figure below, the number of purple urchins counted by PISCO divers has spiked in the last few years at a monitoring site along Cannery Row.

These purple urchins were already readily visible to divers, ranging in size from 2-5 cm in diameter, and therefore had recruited 1-3 years before, as early as summer 2012.

So a boom in purple sea urchin recruitment occurred, and it took a couple of years for divers to actually see them (urchins <1 cm are both hard to see underwater and use cryptic habitat). As these urchins were growing, another event happened: the Blob. Warm water sitting off the coast of the eastern Pacific contributed to very high sea surface temperatures beginning at the end of 2013 and lasting until early 2016, when a strong El Niño event added to the nearshore warming.

Giant kelp generally does not do well in warm waters, and when growth is reduced there is less drift kelp. As they grew, densely packed purple sea urchins were forced to emerge from their cracks and crevices – quarters were becoming tight – and as they grew they need more kelp, right when kelp was scarcer due to the warm water events.

The emergent urchins began to graze on kelp directly, which leads to kelp loss and weakening, such that damaged kelp are more easily removed by swell. These direct and indirect effects further reduced kelp cover, creating a feedback loop.

And what about the sea otters?

Sea otters are important predators of sea urchins. Seminal research by Dr. Jim Estes, USGS and UC Santa Cruz, in the Aleutian Islands demonstrated that otters can control urchin populations, and areas that had been re-occupied by sea otters quickly shifted from urchin-dominated systems to lush kelp forests.

“I find it especially interesting that this phase shift occurred in areas where sea otter densities are at or near carrying capacity. That’s counter to what I’ve seen elsewhere in the North Pacific, and what I would have expected in central California,” says Dr. Estes.

Dr. Estes notes there may be two reasons why sea otters have not started feasting on the purple urchins.

“From what my colleagues and I have seen and documented in the western Aleutian Islands, sea otters are strongly size selective for larger urchins, avoiding consumption of the smaller size classes entirely.” It is not known if sea otters in central California are also size-selective.

“We also have documented a high degree of dietary individuality among sea otters in central California” said Dr. Estes. “Most individual otters consume few or no urchins, which together with their high site fidelity and the relatively low population density might result in areas where urchins are free from otter predation, at least for periods of time.” But otters are known to opportunistically switch to atypical prey when abundant.

The spatial extent of urchin spread and kelp forest loss in central California is unknown. We also do not know how long this increase in urchins will persist.

“I have seen tremendous large scale geographical variation in the rate at which urchin barrens shift to kelp forests with the reestablishment of sea otters. In the western Aleutian the switch takes decades whereas along the Alaska Peninsula, southeast Alaska, and British Columbia, the switch occurs almost immediately after otter reestablishment. I think this results mostly from the interplay between urchin recruitment dynamics and size selective predation,” says Dr. Estes.

In the meantime divers from PISCO will continue to collect data and monitor kelp forests, whether the kelp is there or not.

For questions about this article, please contact Dr. Steve Lonhart at NOAA’s Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary.

May 15, 2018 press release from CDFW related to recreational purple urchin harvesting in Sonoma and Mendocino counties.