Overview

In terms of sheer number and diversity, invertebrates rule the sanctuary. These spineless creatures make up about 95% of all described species of animals. But in the marine environment, the magnificent nudibranchs, glowing jellies, and swarming krill are often overlooked while the charismatic whales, seals and sharks steal the spotlight.

A diversity of invertebrates can be found in all habitats within the sanctuary. Pacific mole crabs, Emerita analoga, polychaete worms, and beach hoppers, Megalorchestia spp., inhabit the sandy shores; lion’s mane jellyfish, Cyanea capillata, pteropods (sea butterflies), voracious arrow worms, and krill drift in the open waters; and owl limpets Lottia gigantean, sunflower sea stars, Pycnopodia helianthoides, and giant green anemones, Anthopleura xanthogrammica, live on the rocky shores. In the sanctuary’s rocky intertidal regions alone, over 320 species of invertebrates are found.

One of the most important components of the sanctuary’s food web is the euphausiid shrimp, or krill. These invertebrates are so critical to the functioning of the ecosystem that, in 2006, a federal ban was proposed that prohibits commercial fishing for all species of krill in the Greater Farallones and other west coast federal waters.

Non-native invertebrates have also made their way to the Greater Farallones. These introductions are a major concern due to the sanctuary’s close proximity to the highly invaded San Francisco Bay. There are currently almost 150 species of introduced marine algae and animals that have been identified in the sanctuary. Invasive invertebrates, such as the green crab, Carcinus maenas, make up over 85% of all introductions in Gulf waters. They threaten the abundance and/or diversity of native species, disrupt ecosystem balance, and threaten local marine-based economies.

Open Water Invertebrates

In the open waters of the Greater Farallones, krill and copepods abound. Copepods, like crabs, are crustaceans. They spend their entire life as tiny zooplankton, drifting with ocean currents, and serving as food for other invertebrates and fish. Argued by some as the most important group of crustaceans, these one-eyed arthropods make up more than 70% of the zooplankton in the open ocean. However, in upwelling regions like the Greater Farallones, both copepods and krill can dominate the zooplankton. Much larger than their copepod cousins, krill are shrimp-like crustaceans that are approximately a half inch to two inches in length. They are omnivores that eat phytoplankton, copepods, and even fish larvae and in turn are eaten by many predators including salmon, seabirds and marine mammals. In the Greater Farallones, the two most abundant species of krill are Thysanoessa spinifera and Euphausia pacifica. T. spinifera is the dominant krill species over the continental shelf in the Gulf, and E. pacifica lives in deeper water at the edge of the shelf and over the continental slope. During the upwelling season, T. spinifera forms daytime swarms at the surface of up to 75,000 animals per cubic meter.

Intertidal Invertebrates

Near the shoreline, between the tides, almost every taxonomic group of invertebrate can be found. This diversity is due to the abundance of food produced by coastal upwelling, and the variety of habitats available along the shores of the Gulf. There are exposed rocky shores, marshes and mudflats, and sandy beaches – all of which support their own characteristic group of invertebrates.

On rocky shores, turban snails and limpets graze on algae while ochre sea stars, Pisaster ochraceus, prey on barnacles, snails, limpets, and mussels. In comparison to the rocky intertidal, the sandy shores of the sanctuary are seemingly void of invertebrate life. Here, invertebrates seek protection beneath the shifting sands. One dominant invertebrate, the Pacific mole crab (or sand crab) lives buried in the sand, between the waves, collecting small plankton with its feathery antennae. Though small, these mole crabs are important to the beach ecosystem. They are herbivores and serve as a vital link in the sandy beach food web. With the help of thousands of student volunteers annually, the Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary and its partners survey the abundance and distribution of mole crabs and rocky intertidal invertebrates along the shores of all California’s National Marine Sanctuaries through a collaborative program called LiMPETS (Long-term Monitoring Program & Experiential Training for Students).

Monitoring

The following list includes some of the projects underway in the sanctuary. Please click on the Projects tab at the top of this page for more information.

Beach Watch

This long-term beach monitoring program’s objective is to develop status and trend information on the sanctuary’s shoreline biological resources. Trained volunteers conduct surveys every two to four weeks. Surveyors document living and dead wildlife; restoration recovery; visitor-use patterns, wildlife disturbance and violations; chronic and catastrophic oil pollution; and detection of ecosystem changes such as El Niño and upwelling events. Since 1993, volunteers have regularly monitored sanctuary beaches documenting wildlife, oil spills and seasonal changes along the shore.

The Duxbury Reef Restoration Program

This sanctuary program analyzes visitor data, determines baseline species diversity patterns and abundance on the reef, and identifies high- and low-impact areas regarding visitor use.

Long-term Monitoring Program and Experiential Training for Students (LiMPETS)

LiMPETS is a program for middle schools, high schools and other volunteer groups; it was developed to monitor rocky intertidal and sandy beach areas of California’s national marine sanctuaries.

The sanctuaries and their partners monitor the abundance and distribution of major intertidal biota, sand crabs and other species to increase awareness and stewardship of these ecosystems. Various data collection procedures include transects, random quadrat counts, total organism counts, sex determination and size measurements. Data are collected so that interested groups working with the sanctuaries’ education staff can follow long-term changes.

Sandy beach monitoring in the California marine sanctuaries focuses on the Pacific mole crab (or sand crab) – a common inhabitant. Sand crabs, which filter-feed plankton from the water, are important organisms in this ecosystem. They are eaten by coastal birds and sea otters.

Sand crabs are used by humans as bait for fishing and have been used as indicators of the pesticide DDT and the neurotoxin domoic acid. The sand crab is also an intermediate host for a number of parasites, including acanthocephalans (thorny-headed worms), which affect threatened sea otters and Surf Scoters.

Sanctuary Ecosystem Assessment Surveys (SEA Surveys)

SEA Surveys are designed to investigate the relationship among hydrographic conditions, physical features and the distribution and abundance of marine organisms in the Greater Farallones. These surveys include counts of marine turtles, birds and mammals along set transect lines.

One component of the Farallon SEA Surveys is to assess biological productivity (chlorophyll-a; phytoplankton species inventory; euphausiid abundance and distribution; distribution/abundance of jellies; assessment of drift algae). SEA’s plankton tows and Harmful Algal Bloom assessments will be used to sample for introduced species as well as native populations.

The Partnership for Interdisciplinary Studies of Coastal Oceans (PISCO)

PISCO is a collaboration of scientists from four universities (Oregon State, Stanford, UC Santa Barbara and UC Santa Cruz) that explores how individual organisms, populations and ecological communities vary over space and time.

PISCO has initiated a massive effort to monitor the rocky shores in and around the sanctuary. It is involved in a large-scale, long-term study of the patterns of species diversity in these habitats and the physical and ecological processes responsible for structuring these communities.

Distribution and Abundance of Marine Birds, Mammals and Zooplankton Relative to the Physical Oceanography of the Greater Farallones and Cordell Bank

PRBO Conservation Science scientists, in partnership with University of California-Bodega Marine Laboratory and the Cordell Bank and Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuaries, have been investigating the spatial and temporal relationships among krill, krill predators and oceanographic processes in the Greater Farallones and the region surrounding Cordell Bank. This project aims to 1) understand the effects of varying oceanographic regimes on predator-prey relationships and food-web dynamics in the central California region and 2) provide a scientific basis for the design and implementation of a marine protected area (MPA).

Research cruises were conducted winter, spring-summer and fall (three to five cruises/year) from 2004-2007. This study has shown large inter-seasonal and inter-annual differences in lower trophic level abundance as well as predator presence in the sanctuaries. Data have allowed scientists to begin to develop a picture of how mobile marine organisms may benefit from a pelagic marine reserve within the highly productive areas of the California Current marine ecosystem.

Wind to Whales

This project, through the Center for Integrated Marine Technologies (CIMT) at the University of California Santa Cruz, uses emerging technology to assess the processes underlying the dynamics of the coastal upwelling ecosystems along the California coast. The project includes study of primary production, nutrient flux, harmful algal blooms and the effects of these on the distribution, abundance and productivity of organisms at higher trophic levels, including squid, fishes, seabirds, sea turtles, pinnipeds and whales.

Photos

Maps

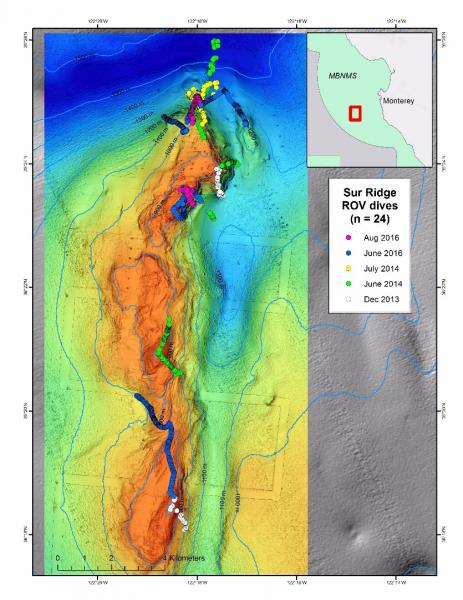

ROV Dives on Sur Ridge Through August 2016

[View Larger]